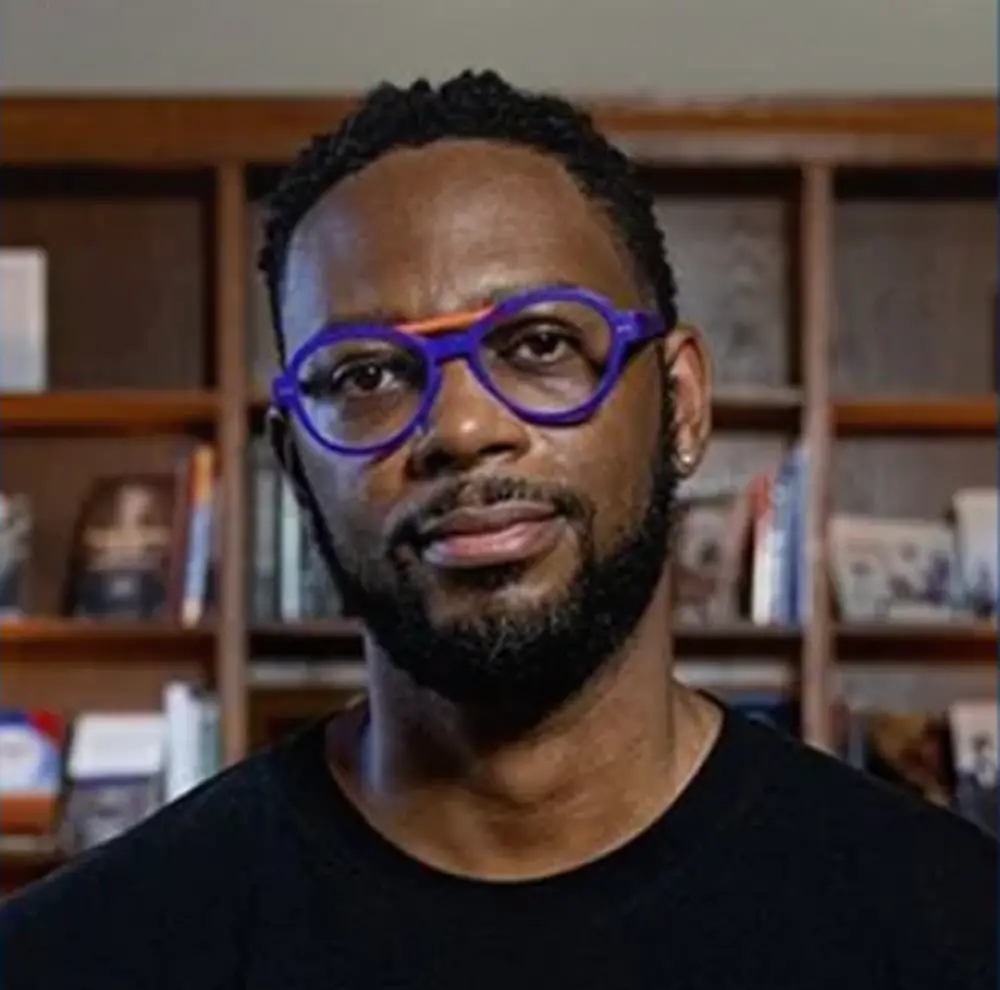

Humor is deeper than a means to make us laugh. Luvell Anderson, a professor of philosophy at the U of I, researches the social context behind the things that we find funny—or not—to learn more about how people use comedy to inspire reflection and deal with sensitive subjects.

Anderson worked previously as a musician. While studying at Rutgers, however, Anderson found philosophy to be very similar to musical composition and decided to enter graduate school. That eventually led to his faculty position at Illinois, where his research focuses primarily on social philosophy and the intersections of race, humor, and language.

“Thinking about humor properly requires thinking about our emotions, how our language works in different contexts, social and political implications, aesthetic considerations, psychological aspects, race, gender, disability, class, and sexuality, and so much more,” said Anderson.

In a recent talk on campus titled “Laughing at the Racial Wealth Gap on Black American Television,” sponsored by the Department of Communication, Anderson used Black-focused television as a medium for examining satire. “African American satirical television has been a forerunner at taking aim at social issues, especially the racial wealth gap,” said Anderson.

In his talk, Anderson invited the audience to think about “how the intersectional stereotypes of white wealth and POC (person of color) poverty and specifically Black poverty are explored within the realm of black American comedic television.” He showed the audience several examples of comedy skits and satire and how they bring attention to or critique the racial wealth gap.

In his talk, Anderson shared a quote from author Ralph Ellison, author of “Invisible Man,” claiming that it is critical for us to laugh at the racial wealth gap.

“For by allowing us to laugh at that which is normally unlaughable,” wrote Ellison, “comedy provides an otherwise unavailable clarification of vision that calms the clammy trembling which ensues whenever we pierce the veil of conventions that guard us from the basic absurdity of the human condition.”

Anderson also spoke about the importance of context. He shared a quote from author and Carnegie Mellon professor Jason England who shares how time and setting play a role in satire.

“If an author discusses delicate topics like war or domestic violence, it’s best to set such things in the past, or in a foreign country, so the reader can experience the rush of moral rectitude without feeling too discomfited by implications of their personal connection to it,” said England.

Anderson’s own critique of satire looked at two different categories. First, Anderson looks at whether satire is used in a way that is benign or aggressive.

“Benign humor arouses attention while eliciting a chuckle, whereas aggressive humor is provocative and makes an audience cringe,” said Anderson.

Then, he looks at whether the satire targets the institution or an individual. “The satirical target can be either an individual’s vices and foibles, or an institution’s features,” said Anderson. In some cases, he said, the individual (in television often a character) may stand as a clear representative of the institution, embodying it.

Anderson analyzed an excerpt from “Chappelle’s Show” on Comedy Central, featuring comedian Dave Chappelle, which originally aired in the early 2000s. The sketch is titled “Reparations for Oppression” and features a fake news show reporting on the effects of Congress paying over $1 trillion to African Americans as reparations for slavery. From depicting fictional street scenes to shifts in the stock market, Anderson said, the sketch addresses a controversial topic by playing upon stereotypes of Black people making “poor and unintelligent” decisions in the ways that they spend the reparation money.

One of the jokes brings attention to the fact that there are not many banks in areas where Black people live because of the racial wealth gap. The skit suggests however that the reparation checks will inspire banks to reconsider moving closer to Black neighborhoods.

“This moment is an instance of benign institutional criticism that elicits a chuckle but avoids being too provocative or condescending,” said Anderson. “However, the opportunity to unpack this complex cycle with a more nuanced joke is dismissed with the line ‘banks hate Black people.’ The joke’s stereotypical nature threatens to invite audiences to laugh at, instead of with, Black people and their unjust predicament.”

Anderson is also part of a podcast, SNL 101: Saturday Night Live in the Classroom, that examines the content of Saturday Night Live episodes. The podcast is part a project of the PoSH (Philosophy, Psychology, and Pedagogy of Satire and Humor), an interdisciplinary lab group which Anderson cohosts with Charisse L’Pree, professor of communication at Syracuse University.

Together, they examine content from SNL episodes through a critical social scholarly lens. They cover a wide range of topics including race/ethnicity, satire/humor, gender, stereotyping, feminism, and more.

In one podcast, for example, they look at episode 15 of season 50 of SNL, hosted by Lady Gaga. One of the skits introduces the fake character of Lord Gaga as Lady Gaga’s husband who appears for an interview on Weekend Update. The Lord Gaga character is a pre-20th century English nobleman, and the skit satirizes his overbearing masculinity while the host broaches the idea that Lady Gaga’s music makes more money than his textile business, to Lord Gaga’s disbelief.

“Can you imagine, Colin, a man whose wife makes more money than he?” Lord Gaga cries, to the laughter of the SNL crowd. “Oh, the shame he would feel!”

SNL 101 also analyzes commodity feminism, in which companies leverage the social expectations of women in order to sell products. The podcast examined the satirical SNL advertisement for “Easy Run” mascara, marketed as being particularly runny and susceptible to moisture.

“Sometimes, don’t you kind of want it to (run)?” Says the fake actress. “You know, for attention.”

Anderson is currently working on two books. The Philosophy of Race and Racism: The Basics is an introductory into the basic issues in philosophy of language and racism. He said this book is for undergraduates and a more general audience. The book is in the process of being published with Routledge Publishing.

His other book, The Ethics of Racial Humor, centers on the intersections of his main research interests. He explores three basic questions in the book: What is racial humor? Why is racial humor funny? When does racial humor go too far? Anderson hopes to finish the rewriting process for this book by this fall.

Anderson is also a co-editor for The Routledge Companion to the Philosophy of Race (2017).

“One of the main things that excited me about coming to U of I is that it is a great university filled with so many interesting people doing meaningful work,” said Anderson. “I’m inspired by the chance to learn from and draw inspiration from people across diverse fields.”

Editor's Note: This story originally appeared on the College of LAS website.