"Explanation, Control, and Indeterministic Free Will"

I begin by sketching a minimalist libertarian account of free will, one that is neutral as between so-called event-causal, agent-causal, and even certain noncausal accounts of the metaphysics of free choice and action. On this account, free choices are governed by objective probabilities. I then consider four recent control- or explanation-based objections to any such probabilistic account and argue that they do not succeed. I will end by arguing that, contrary to widespread assumption, the thicker metaphysical accounts that many deploy in developing distinctive responses to adequacy objections are not so much rival theories of freedom as one account of freedom developed within different theories of the root categories of substance, property, and causation, which theories are to be adjudicated on independent grounds.

"The Possibility of Respect: Towards An Ethics of Difference"

In this talk, I explore the connection between understanding persons and respecting them. This connection is the focus of my current book project and the culmination of several years of work. But instead of delving into the nuances of the central theoretical claims of this project, in this talk I will explore what motivates it. In doing so, my goal will be to upset some longstanding philosophical biases towards rationalist and rights-based theories of respect, to help clear conceptual space for my alternative claim that understanding persons sometimes constitutes a way of respecting them. The upshot, I will argue, is a view about respect that is focused on persons in their individuality, and the promise of an ethics premised on difference.

"Reid on Powers and Abilities"

As opposed to some of his predecessors (especially Locke) and contemporaries (especially Hume), Reid believes that the mind is active, by contrast to the body, which is fully passive. He claims that the mind is “properly active”. The main purpose of this paper is to understand what exactly the distinction between power, operation, and ability amounts to, according to Reid.

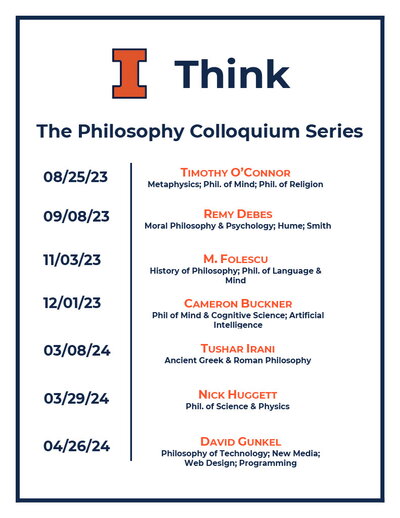

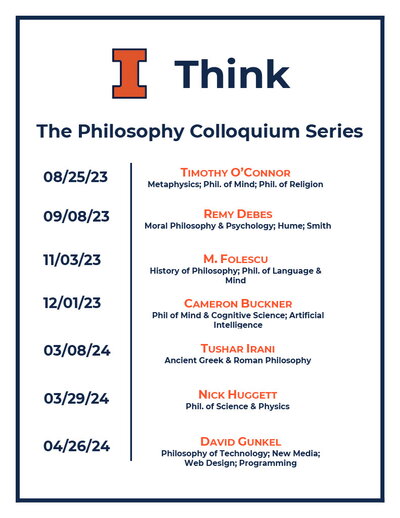

Cameron Buckner

University of Houston

Friday, December 1st, 2023

3-5 p.m. CDT

Gregory Hall 223

Moderate empiricism and machine learning

In this talk, I outline a framework for thinking about foundational philosophical questions in deep learning as artificial intelligence by linking its research agenda to that of classical empiricist philosophy of mind. Critics of deep learning frequently paint it as beholden to a radical form of empiricism found in the radical behaviorists like John Watson and B. F. Skinner, but most research in deep learning fits better with a more moderate and historically grounded form of empiricism found in figures from the history of philosophy. I rebut the radical caricature by explicating the more moderate form that can be reverse engineered from most headline achievements and extracted from position papers by major figures in deep learning. What is missing from the radical caricature—but highlighted by both mainstream historical empiricism and deep learning—is the critical role played by interactions amongst active, general-purpose faculties (like perception, memory, imagination, attention, and empathy--which I illustrate by exploring the faculty theories of Aristotle, Ibn Sina, John Locke, David Hume, William James, Adam Smith, and Sophie de Grouchy). Tying deep learning to empiricist faculty theories offers benefits to both disciplines: computer scientists can continue to mine the history of philosophy for ideas and targets to hit in creating more robustly rational artificial agents, and philosophers can see how some of the historical empiricists’ most ambitious speculations can be realized in specific computational systems.

Plato’s Account of Being as a Theory of Predication

The interrelatedness of the forms is the signal feature of the metaphysical picture that Plato develops in the Sophist, but it’s also an especially crucial claim in understanding how he believes the forms stand to one another in subject predicate relationships. I argue in this paper that Plato’s account of being as “change and rest both together”—the so-called “children’s wish” at 249c-d in the Sophist—is not just a metaphysical theory but functions in addition as a theory of predication. The account basically does double duty: it underwrites Plato’s belief in the interrelatedness of the forms while also explaining a range of predicative statements at the heart of many of his most celebrated philosophical views—from the essential relationships he draws in defining the soul as a principle of self-motion, for example, to analogical relationships that compare the soul to a city. The children’s wish thus explains not only a form’s possession of a variety of essential features but also Plato’s use of poetic devices for philosophical purposes: it provides the metaphysical backing required for philosophical image-making. As a theory of predication, I suggest it represents a kind of logic that makes sense of both the discursive reasoning that’s characteristic of philosophical inquiry and the figurative reasoning that Plato regards as conducive to philosophical understanding.

Person, Thing, Robot: A Moral and Legal Ontology for the 21st Century and Beyond

Robots are a curious sort of thing. On the one hand, they are designed and manufactured technological artifacts. They are things. Yet, and on the other hand, these things are not quite like other things. They seem to have social presence. They are able to talk and interact with us. And many are designed to mimic or simulate the capabilities and behaviors that are commonly associated with human or animal intelligence. Robots therefore invite and encourage zoomorphism, anthropomorphism, and even personification. In his new book Person, Thing, Robot (MIT Press, 2023), David J. Gunkel sets out to answer the vexing question: What exactly is a robot? Rather than try to fit robots into the existing moral and legal categories by way of arguing for either their reification or personification, however, Gunkel argues for a revolutionary reformulation of the entire system, developing a new approach to technology ethics that can scale to the unique opportunities and challenges of the twenty-first century and beyond.